By Kendra Gaede

My mum, who turns 80 today, still remembers the taste of the oral polio vaccine given to her atop a sugar cube in the 1950s.

She also remembers the collective sigh of relief of at the release of the vaccine and its importance in the fight against a disease that indelibly ravaged children and their families forever. This memory of gratitude gets lost in the generations after the Boomers.

Human beings have a tendency to disbelieve what they have not themselves experienced. When you’ve benefitted from decades of polio-free living, its easy to convince yourself the vaccine is no longer necessary. But as we’re seeing with the spread of measles in Texas, the willingness to disbelieve the knowledge and experience of those who came before us can cause tragic consequences.

Up until now, anti-vaxxers have benefitted from the collective immunity of previous vaccinated generations to not get sick. Vaccines work – history has proven it again and again – but they can’t work if you don’t get one.

We can surmount our experiential ignorance by becoming students of history and learning from the past.

Speaking of which, it’s a tough go for students of history right now. Humanity seems determined to repeat itself with willful ignorance.

As we lose the last of our WWII veterans (the Greatest Generation), the Quiet Generation and early Baby Boomers, the world’s collective memory of the horrors of war and global conflict is lost along with them.

So when racism, hypernationalism, facism, and purposeful destabilization of alliances and economies begin to occur again, historians can’t help but ring the alarm bell and for good reason – no one needs a reboot of the conflicts of the first half of the 20th century.

Genealogy and genealogists can help defuse the current political climate by reminding people of a simple truth – we are all related, despite borders, languages, trade barriers and the agendae of world leaders.

My own work studying genealogies of people with ancestors from Western Canada has proven international. It’s rare to find families who have been in one country for four generations (raising the difficulty of exercises toward genealogical accreditation, let me tell you).

The Fur Trade operated before the western U.S./Canada border even existed, and Rupert’s Land once stretched below the 49th paralell. Arguably, parts of North Dakota and Minnesota could have been part of Canada.

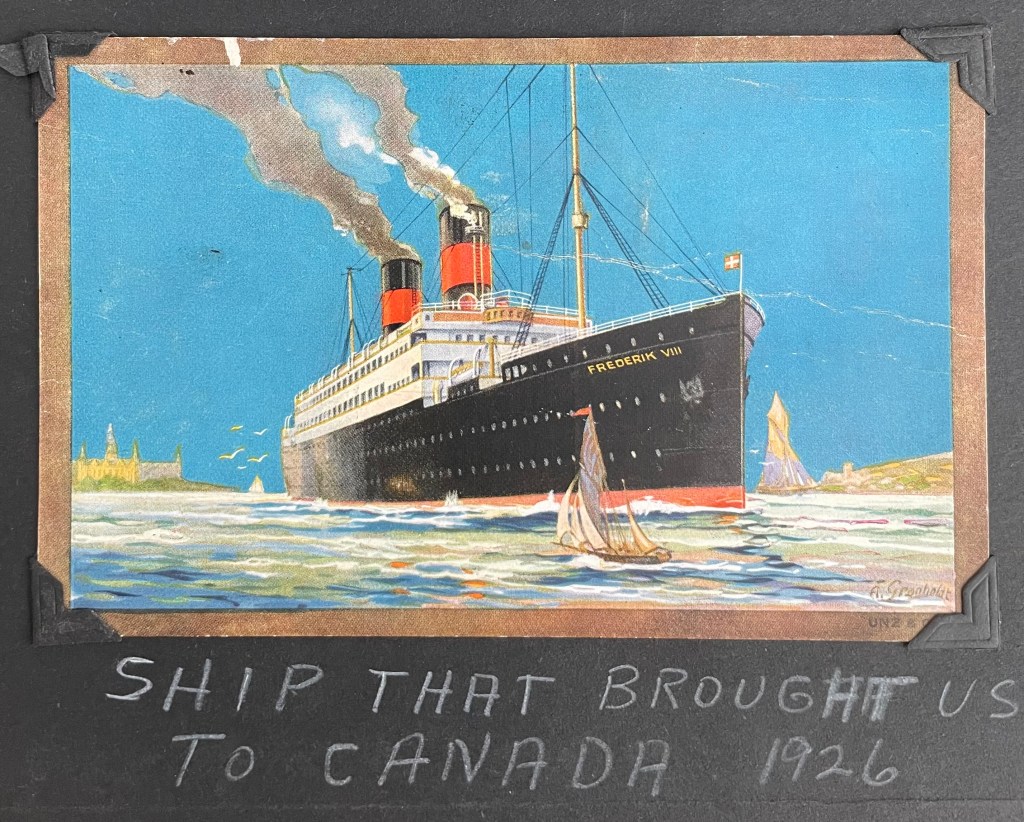

Immigration stories are some of my favourites to research. Most of of us have immigrant ancestors – yes, even Donald Trump, whose grandfather, Friederich Drumpf, immigrated to the United States in 1885 to avoid military service in Germany. (A family tradition?) Plenty of American families first arrived on North American shores via Canadian immigration and vice versa.

People choose to immigrate due to things like famine, oppression, and economic instability. I’m proud of my immigrant ancestors. Immigrant labour (my ancestors and yours) has fueled North American economies for at least 200 years. To fear the immigrant is to fear ourselves.

And to anyone who is not Canadian and a historian, let me tell you that the tariffs and threats to our sovereignty smell a lot like Germany in 1938. How do I know that? I read books. Lots of ’em. All the time.

And as president Bill Clinton once said:

“Surely, the human genome is our shared inheritance, and it is fitting and proper that we are all working on it together.”

Let’s work on this together. Support your Canadian genealogist colleagues and disperse this historical truth: Canada and the U.S. work better as respectful friends.